News that acclaimed writer Thomas King is not, in fact, Cherokee has sent shockwaves through Indigenous communities in North America. A genealogist working with the US‑based Tribal Alliance Against Frauds (TAAF) reported finding no evidence that King has Cherokee or other American Indian ancestry. King has accepted those findings, publicly stated that he is not Indigenous and says he intends to return the National Aboriginal Achievement award he received in 2003, an honour created to recognise First Nations, Inuit and Métis people.

It would be easy for us to shrug and say – “That’s Canada’s problem.”

But the questions King’s story raises land very close to home, especially as the global 16 Days of Activism against Gender‑Based Violence campaign turns our attention to the safety of women and girls.

The 16 Days campaign asks us to look not only at bruises and police call‑outs, but at the quieter harms that keep women and children unsafe. Economic control and cultural erasure rarely make headlines, yet they still push Aboriginal women and girls towards danger. Indigenous identity fraud is one of those quieter harms.

“Identity fraud” can sound dramatic, even American. In Canada and the United States there is now a common term for serial false claimants (“Pretendians”) and a growing body of work on “race shifting”, where non‑Indigenous people begin identifying as Indigenous, often as scholarships, jobs, contracts or prestige become available. Aboriginal scholars here have described similar “race shifters” and “box‑tickers” in Australia, warning that such claims can funnel places in universities, jobs, housing and financial assistance away from Aboriginal families.

For Aboriginal women in the New England, those places are not abstract. They are often the difference between staying in a violent household and being able to leave. A scholarship to the University of New England, a traineeship in Tamworth or a leadership program in Glen Innes can put food on the table, pay for petrol to get to court and show kids that a different life is possible.

When non‑Indigenous people slide into those spots, our girls and their mums are the ones pushed to the back of the queue.

Picture a local high school in Armidale or Moree. There might be one or two scholarships earmarked for Aboriginal students each year. On one side of the shortlist is a Year 12 girl who has done the school run for her little brothers, held down a casual job at the servo and still turned up for tutoring, all while living with violence at home. On the other side is a student from a comfortable family who has only recently started claiming Aboriginal heritage, based on a hazy family story that has never been tested against proper records / genealogy.

If the second student gets the scholarship, nothing technically illegal has happened. The paperwork is in order… but a girl who needed that opportunity to get safe housing in Armidale or Newcastle may find herself stuck. That is how identity fraud (or even just careless box‑ticking) becomes another form of gender‑based violence. It keeps women and children in harm’s way by quietly diverting life‑changing resources.

We do not like to say this out loud because we are polite country people and we do not want to start witch‑hunts. No one wants to be the person who questions someone else’s identity.

And as Thomas King’s case reminds us (if you believe his side of the story), sometimes people genuinely believe family stories that turn out not to be true. His situation is supposedly different from someone deliberately inventing an identity for cash or status…. but even sincere mistakes cause harm when institutions never check (loss of opportunities to break the poverty cycle / family violence, etc.).

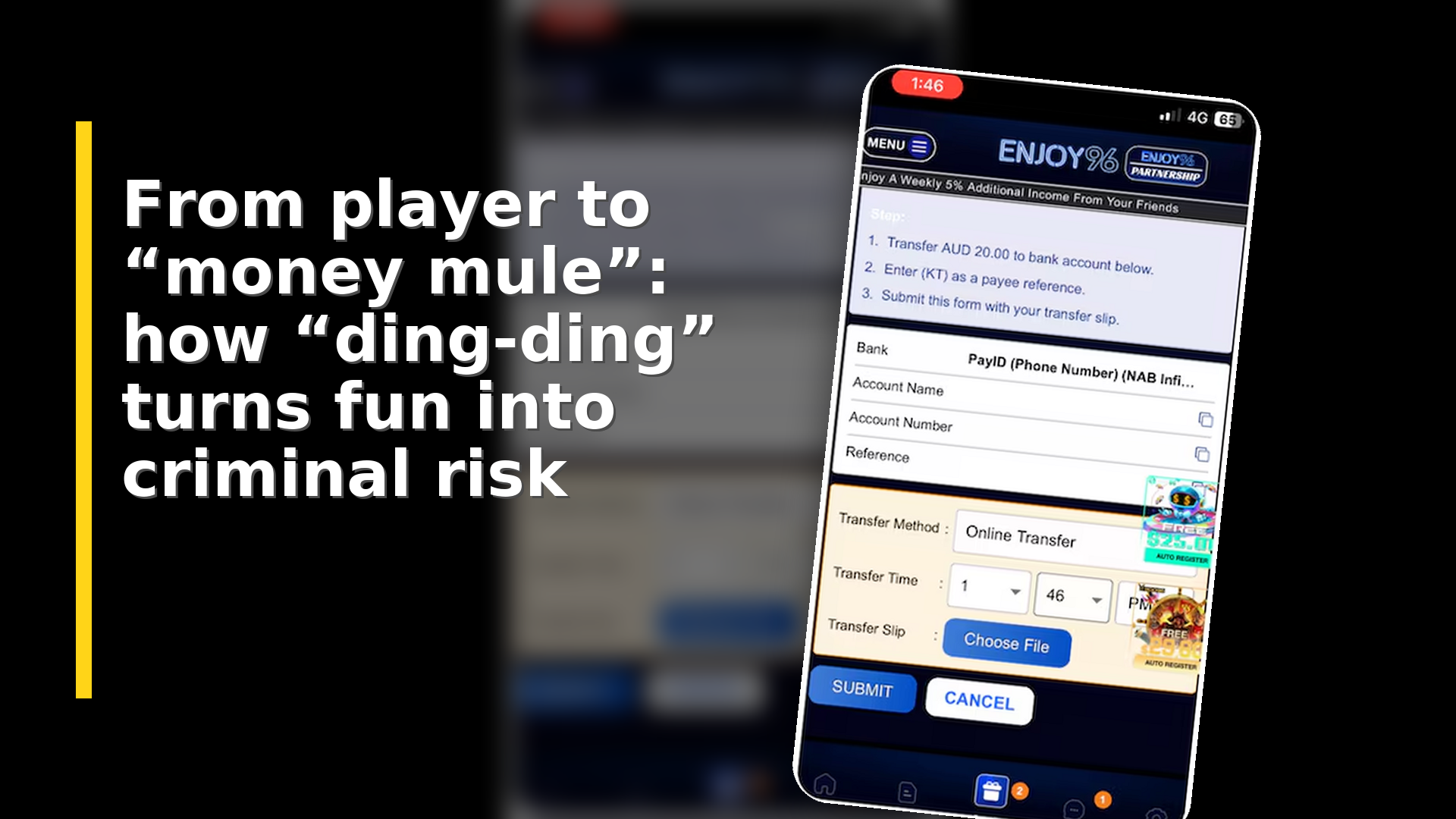

Thus, the answer is not to subject every Aboriginal person to humiliating scrutiny. Community has always known who belongs. The problem is systems that treat identity as a box on a form e.g. Australia Government has awarded ovre $7 billion to “Indigenous” businesses.

When scholarships, awards or “Indigenous‑only” roles are on offer, decision‑makers should be guided by community, not just self‑identification.

That might mean asking for confirmation of their family lines / genealogy or prioritising applicants who are known and active in local community, not just those with a neatly written application. The widely‑used three‑part test (descent, self‑identification and community recognition) already points in this direction; it just needs to be applied consistently.

We also need better spaces for honest conversations.

Non‑Indigenous people who have grown up with romantic family myths about a “Cherokee princess” or a “great‑grandmother who was Aboriginal” need somewhere to take their questions that is not the scholarship application form. Good‑faith curiosity is one thing; using a half‑remembered story to get your child a bursary that was meant to keep another girl safe is another.

Violence against women and children is not just fists and threats.

It is also the slow theft of opportunity, the quiet shuffling of resources away from those who need them most. As we mark the 16 Days of Activism, we need to remember that protecting Aboriginal women and girls means defending the spaces set aside for them. That includes shining a gentle but determined light on Indigenous identity fraud… before it steals any more of our daughters’ futures!

Discover more from Indigenous News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.